On a hot March morning, pieces of Aloha Stadium lie on the asphalt like items at a yard sale: two pay phones, rows of orange stadium seats, concessions signs, section signs, bathroom signs, five-foot-tall photos of University of Hawaii football players and tiny T-ball players that used to hang over the entrances to the stands. At the box office, online bidders pick up their winnings: six-inch squares of turf, 1996 Pro Bowl programs, flyers from the 2018 Snoop Dogg and Cardi B concert.

Gary Viela straps his season-ticket seats from row 29 into the bed of his pickup truck. They've been in his family since the stadium opened in 1975. "My father worked for the state, so he and his staff all decided to buy seats together," he says. "When my father passed away, I just kept the seats-we just stayed in the same seats from the time the stadium opened till the time it closed. We'd always meet here for the games, we'd always tailgate together. Then at the last game of the season, I'd buy Dungeness crab and steaks and we'd boil the crabs at the stadium. People would ask me to buy some."

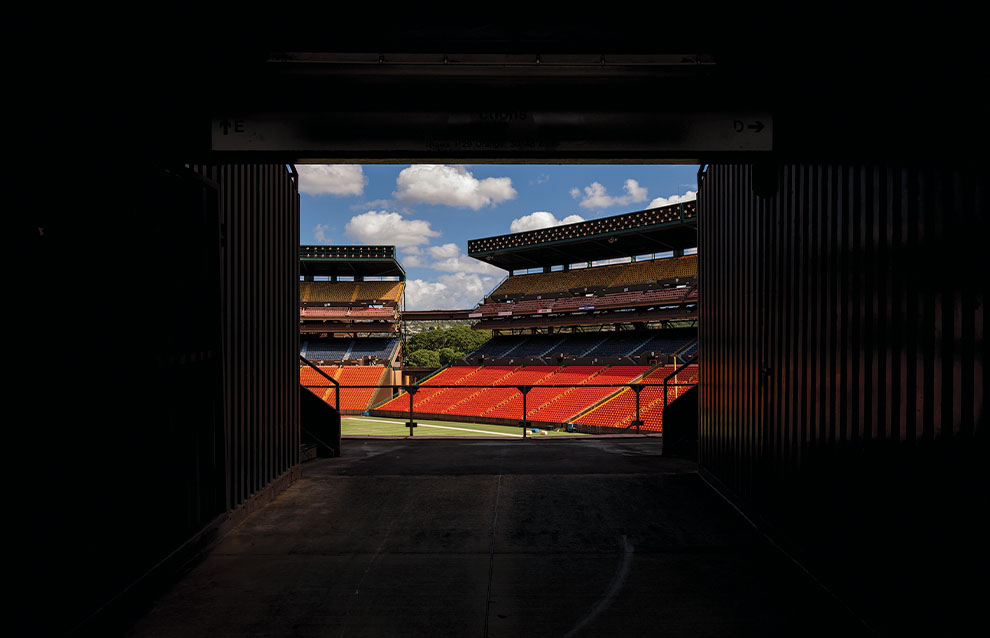

|

|

Left, with the closure of Aloha Stadium (RIGHT), its contents, including seats, are being auctioned off. Right, a vintage photo goes home with the highest bidder.

Viela plans on putting the seats on his patio. "I have a picture of my mom and dad sitting here," he says. "I'm gonna blow it up and slap it on the seat," so even though his parents and Aloha Stadium-at least the one he knows-are now gone, he can still watch the games from the seats they once sat in. "To the very end, they came to the game."

As the forty-eight-year-old Aloha Stadium faces demolition, people are buying up pieces of nostalgia. In the parking lot they reminisce about the glory days, when June Jones and Heisman runner-up Colt Brennan led the Rainbow Warriors to the Sugar Bowl, when the lot was so packed you'd have to park at Pearl Harbor; about the saimin at the concession stands; about the other season-ticket holders they would see only at games, every year for forty years, long enough to watch the kids grow up and exchange end-of-the-season Christmas presents. "They wasn't the best seats," says Troy Hiura, picking up his seats from the north end zone, "but I just loved those people around us for forty years."

Even if you aren't a sports fan living in Hawaii, you probably have a memory of Aloha Stadium. A friend remembers skydivers parachuting in to tell kids not to do drugs during a statewide DARE day. Another remembers vomit raining down from the upper deck at a Bruno Mars concert. Another can still smell the hot dogs as she worked the concession stand for a high school fundraiser. I remember the tailgate parties with smoke meat, laulau, opihi (limpets) on the grill and apple banana moonshine. You didn't even have to be at the stadium to feel its presence-when I worked at a restaurant in 2006, during the Colt Brennan era, we knew that we might as well close for dinner on game nights, it was so slow. In those years almost fifty thousand people-about 20 percent of Honolulu's population-would be in the stadium on Saturday nights, the greatest concentration of people in the state over a three-hour span.

Glory days: University of Hawaii former football coach June Jones and quarterback Colt Brennan strategize during a game against USC at Aloha Stadium in 2005. “The best thing I liked was being able to tailgate,” says Viela of the UH games. “We always had a regular area right by the entrance—and then when Colt Brennan started to play, it was so crowded we ended up parking in Pearl Harbor.” PHOTOGRAPH BY KIRK LEE AEDER

Kelly Tam Sing was a kid in the early '80s running up the steep stairs of Aloha Stadium when he tripped and slammed his face on the concrete, breaking his tooth and bleeding. His dad, knowing that his dentist would be at the stadium, paged him over the stadium PA. The dentist came, albeit grumpy about a work call during the game. Back then, before televised games and the internet, everyone was at the stadium on Saturday nights. It was like Hawaii's living room, even down to the family photos on the wall-a photo of Tam Sing's sister as a young cheerleader hung above the entrance to the north end-zone seats. Sometime in the '80s the images above the entrances were covered by sponsorship signs.

David Brandt, owner of Oahu Auctions and Liquidations, which is handling the stadium auction, rediscovered those images when he was taking down the signs. "It almost shows-not to get too deep-a different era, when we weren't trying to squeeze every penny out of everything, right?" He muses. "Because instead of putting up Budweiser, we put up those photos. It's almost an ohana thing. Like maybe it should have been called Ohana Stadium, not Aloha Stadium."

When Aloha Stadium opened in 1975, it was the Swiss Army knife of stadiums. The stands could slide into an oval for football games, a diamond for baseball and soccer, and a triangle for concerts and other events. At the time it was a cutting-edge marvel: Four of the stadium's six grandstand sections, each as tall as a fourteen-story building and weighing 3.5 million pounds, could slide around the playing field on cushions of air, using technology from NASA's Apollo program. "Even before the University of Hawaii's season-opening football game with Texas A&M last week, there had been a show of another kind of power and agility at the state's new $30 million Aloha Stadium in Honolulu," proclaimed Time magazine in 1975, in awe of the stadium's mechanics. "All it would take to prepare the stadium for baseball next spring is some season-end shoving by the football team."

|

|

(LEFT) Most of the country knew Aloha Stadium as the home of the NFL’s Pro Bowl for thirty-four years, starting in 1980. Here, the Cardinals’ Larry Fitzgerald catches a touchdown pass in the 2009 Pro Bowl. PHOTOGRAPH BY KIRK LEE AEDER (RIGHT) U2 performing in 2006; Bruno Mars broke the Aloha Stadium attendance record set by U2 with three sold-out 2018 concerts in his hometown of Honolulu.

And so the stadium was all things to all people: It was home field for the Hawaii Islanders, Hawaii's minor-league baseball team, before it decamped to Colorado in 1987. It hosted Major League Baseball, rugby matches and professional soccer teams-even Pele, one of soccer's greatest players, flexed his prowess here, scoring four goals against a team from Japan in 1976. The World Cup-winning US women's national soccer team, however, never played at Aloha Stadium-their exhibition match in 2015 was canceled when they showed the artificial turf on the field coming apart, literally, at the seams, deeming it unsafe to play on. (Soon after, the turf was replaced for $1.2 million. "My goal, and people tell me I'm out of my mind," says Brandt, "is to find a buyer who wants to buy the whole thing.")

There were the monster truck rallies, the MMA fights, the concerts-Janet Jackson, the Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson, U2. Add on the high school graduations, and in Aloha Stadium's prime you'd be hard pressed to find a more multipurpose stadium in the country. Football games, both the Pro Bowl and Rainbow Warriors, though, were still its marquee events, with fans peaking at a record 49,651 on November 23, 2007, when UH played Boise State. The stadium, which already rocked during even the most tepid wave, shook like a child's bouncy house as fans stomped their feet while Colt Brennan threw for 495 yards and five touchdowns to lead the Warriors to their first undefeated regular season in the school's history.

But after thirty years, moving the stands wasn't as frictionless as it once was, requiring up to two weeks and $20,000 for labor and equipment rentals each time they needed to be moved. By 2007 the stands were locked into a football configuration. And as UH wins slid, so did attendance. Meanwhile, maintenance problems and costs piled up over the years-what was supposed to be a protective patina ended up being straight-up corrosive rust, earning the stadium the unfortunate moniker of the Rust Palace. In 2019, $350 million was set aside for a redevelopment project, a.k.a. the New Aloha Stadium Entertainment District, which envisioned a brand-new stadium ready by the 2023 football season, plus retail and housing. Now, midway through 2023, the old Aloha Stadium, slated for demolition two years ago, still stands, with no progress on a replacement. In front of the stadium, as part of Oahu's beleaguered rail project, empty trial train cars shuttle back and forth on the new elevated railway, as if a reminder of how long such projects take.

In some ways the most valuable part of Aloha Stadium is its parking lot. Annually, a little over a million people attend the thrice weekly Swap Meet, where more than four hundred vendors and everyday people sell and resell items. Above, Chin Ng, one of the Swap Meet’s longest-running vendors, has been selling knives from his stand for thirty-five years.

One of Aloha Stadium's most profitable sports (if you want to call it that) happens across two miles of its parking lot: shopping. On a recent Saturday morning, about four hundred vendors are set up, selling Laotian sausages and Cajun tater tots, foam plumeria hair clips and real plumeria cuttings, Gamecube discs and fidget spinners, Tahitian black pearls and pearl milk tea, Kona coffee and Starbucks merchandise from the Philippines, Indonesia, Mexico ... and more, so much more bric-a-brac. (One of the auction bidders purchased a stack of boxes filled with lost-and-found clothes that he intends to sell at the swap meet.) It's part flea market, craft fair, farmers market, souvenir shop and, in the outer rows, haphazard garage sale, with items dumped directly on the asphalt. While all other events have ceased at Aloha Stadium, the Swap Meet continues Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday in the parking lot, where it has operated since 1979. It is, after all, one of the stadium's biggest moneymakers, generating around $4 million in revenue a year-one person knowledgeable about the stadium's finances remarked that Aloha Stadium is "the only stadium in the country in which the parking lot is more valuable than the stadium itself."

Quieter success stories have begun here in the lot. Olay Somsanith, a Laotian refugee, began her life in Hawaii selling vegetables at the swap meet. Today, Olay's Thai still operates here, now selling pad thai and papaya salad, and it is one of the most ubiquitous Thai food vendors across the island, open at farmers markets on almost every day of the week while also operating a brick-and-mortar in Chinatown.

"This is one of the last strongholds for old-time people," Chin Ng says, shirtless and yet dapper in his bucket hat and a white handkerchief tied around his neck. He smiles behind rows of knives interspersed with photos of him and his wild boar kills-his stand seems incongruous among the pink plastic lei and plush Spam keychains being hawked around him. Ng is one of the swap meet's longest-running vendors, selling knives here for thirty-five years. "Not too much has changed," he says, in terms of shoppers, with "a good diverse mix of locals and military and tourists. But retail has changed-back in the heyday before the internet, [the parking lot] was all full of vendors." There aren't many sellers left who have been there as long as him, he says. "They are getting far and few, but there's always new entrepreneurs. That's what the swap meet is about." Or life. "Everything changes. The old regime is gone, and then the young blood comes in."

The play clock blazes hot and fantastically bright in Sean Scanlan's garage. In a frenzy of bidding in the Aloha Stadium online auction, he rushed to buy signs ("Stairs Down," "Upper Seating Sections," "U"), turf and stadium seat backs that he's bolted onto his folding chairs. And two play clocks.

After forty-seven years in operation, Aloha Stadium is closed and awaiting demolition. The state has allocated funds for a new stadium, but when construction might begin remains uncertain. “This facility holds a lot of emotions and experiences that are near and dear to people’s hearts,” said stadium manager Ryan Andrews at a recent press conference. “It’s hosted the greatest talent this world has produced … so it’s definitely served its mission in providing great entertainment to the state.”

Sean and his brother Cavan are adamant: Whatever else might have happened at Aloha Stadium-concerts, Swap Meet-it's the football that it was known for. They have an intimate knowledge of the stadium, having played in it, coached in it and watched games from every section. For Aloha Stadium is the rare American stadium where a kid on a Pop Warner team can get turf burn playing on the same field as Tom Brady did when he came for the Pro Bowl. They remember where beer and bathroom lines were the shortest (yellow section), where the best parties were (in the spirals in the south end zone, when there was a bar set up in the base of the stairs), where to sit when the Halawa rains came.

"You want to be on the mauka [toward the mountains] side, but can't be too towards the back because it can blow in on the blues," Sean says, referring to the color of the seats. "Makai [toward the sea] side blues is not bad if you're high up because it just blows down."

"Blue, brown, yellow mauka side's pretty good," Cavan says.

"Yellow better than blue because of the big gap in the roof."

"But if you're orange you're screwed."

"And the poor Mainland guys get cooked, all sunburned every time at the Pro Bowl."

"Shirt off, sunburned."

Cavan divides his Aloha Stadium memories into kid times and fan times. Kid times: carefully tearing the rosters into strips, rolling them and throwing them in the air, along with thousands of other fans, when the Warriors scored. They'd run routes in the parking lot, crashing into cars while their families tailgated, or play touch football on the turf pockets that stuck out from the bottom of the stadium, segments of the baseball turf that were exposed when the stands were moved for the football field.

There were the years when the kid time and fan time overlapped: "As a kid, you had a dream weekend of high school football, and then UH was home. You had the back-to-back stadium Friday and Saturday nights," Cavan says. And then as a fan: "We had seats in every color, every level. We were there for the winless season. We're there for the undefeated season. And those were within ten years of each other."

Sean says, "Well if you're going to be called a fan, you go. 'Fan' is short for fanatic, not fantastical, once-in-a-while thing. You go."

"Afterwards you cruise in the parking lot, finish up the food, talk about the game. That was our communal weekly event, where at least I'd know I'd see you. Because everybody has their lives, but I know I'd see you Saturday. Worst-case scenario, we all hung out for a few hours. One time I remember talking story and come back, it's fourth quarter already."

"Maybe that's you. I was there for the game."